The Tragedy of the Commons, revisited

Hardin was more concise - “Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit – in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons.” Both authors are making a comment about an economic concept called diminishing marginal utility - if you overuse something it becomes less useful. But there is a second unspoken assumption here - that is people are unable or unwilling to think about the common good. Hardin was a devotee of apocalyptic environmentalism. He was a modern Malthusian and like the founder of the movement believed that overpopulation was caused in part by welfare policies. His ideas ignored the effects of pricing and of regulation. Both authors also ignored the human tendency for humans to adapt. Hardin was not an economist but boy was his outlook dour.

For me another contributor to this discussion was Elinor Ostrom, a University of Indiana economist, who thought a little more carefully about the issues on the commons and came to a very different conclusion - She argued that there are plenty of ways to adjust behaviors without top down regulation. She made that argument in a book called Governing the Commons, where she took Hardin’s paper and blew it out of the water with examples of alternative, less intrusive, regimes to reduce the problems of misallocation of resources. For that, she won the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in Economics (the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences) in 2009.

There is a good footnote on Ostrom who had to struggle to achieve her status. When she applied to UCLAs Economics program they rejected her because she lacked Trig. She eventually got on track, completed a doctorate and ultimately married one of her doctoral professors. She and husband Vincent had a marvelous career challenging traditional notions of organization and centralization. Both in her writing and in a couple of chances where I had the opportunity to hear her speak she had a special skill of consistently challenging established interpretations.

As I have thought about the Commons issues I think there is a reciprocal (basically the inverse of the original argument). Hardin had no understanding of the possibility of spontaneous organization - as an “environmentalist” one would expect he had seen many examples of those things happening in nature - but he seems to have missed them all. But if you step out of the apocalyptic bubble you realize that there is a strong case to be made for some inverse logic on Hardin’s argument. Too much regulation can be even worse that too little.

My home state is ground zero for Apocalypticists. California currently spends a quarter of a billion dollars in licensing more than 200 professions; many of those licenses are designed to protect us from imagined ill effects that are supposedly eliminated with state regulation. The Mercatus Center at George Mason University recently ranked California 49th in terms of economic freedom and 50th in regulatory freedom, finding that “California not only taxes and regulates its economy more than most other states, but also aggressively interferes in the personal lives of its citizens.” In addition to its vigilance on all sorts of professions California has lived with the Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) which simultaneously slows down the process of development and adds costs to almost every land decision. Any wonder why the state’s housing is so expensive? Is it a surprise that the state is a center for homelessness?

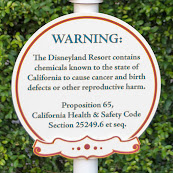

Then there is Prop 65, the annoying proposition authored by Tom Hayden, that requires disclosures about supposed cancer risks on a wide variety of real and imagined dangers. There are some real perils with dangerous substances but the standards in Prop 65 are absurd. For example, Disneyland has a Prop 65 warning which intones that they use substances that are cancer causing - one of those warnings is near a place to buy coffee. The problem with the Prop 65 warnings is that this additional annoying disclosure may indeed reduce concern for really toxic substances. If we know that some of those disclosures are downright silly, how likely are we to have trust in the real risks? Was Hardin a new example of the boy who cried wolf? Certainly Tom Hayden made a career on wolf calls.

Opponents of the Apocalyticists are often characterized as “deniers”. If we want to be fair we should probably shoot back that the Apocalyticists are overly pessimistic about the human propensity to adapt. Does that mean that I do not accept any form of regulation? That is an absurd question - but it suggests that my thinking says we should be equally skeptical of the efficacy of regulation as some are about the human ability to manage their own affairs.

THE BOOK. I have had a couple of friends who have wondered whether Of Course It’s True, Except for a Couple of Lies, is part of the continuing Lucy and the football story. For the past couple of years I have argued that it is about to get published. Well, in the last few weeks, things have started, finally, to change. First, I got solicited b one of the imprints of Simon and Schuster to have them publish the book. I spent a couple of months talking to them but did not like the original proposal they offered me. Then about 2 weeks ago, because of a note on Linked In, I got an inquiry from Forbes. They have a division for first authors. Early in the week, I had a discussion with their rep. The Forbes imprint is not something that fit my needs, they seem to expect that first time authors need a ghost writer. So I restarted the discussion with the S&S people and early in this week signed an agreement for them to publish the book. That imprint makes has distribution through all the normal channels - Apple Books, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, and a host of others in hard copy, paperback and E-Books. The good news is that I think I can see the end of this line. The bad news is that the process will take about 25 weeks from the time that the final manuscript is submitted.